It didn't take very long before new technologies emerged. Less than forty years after the introduction of the Linotype, the foreboding of the future can be found in phototypesetting. In phototypesetting, light projects a type character onto photographic film or photosensitive paper. In a next step, a printing plate is produced.

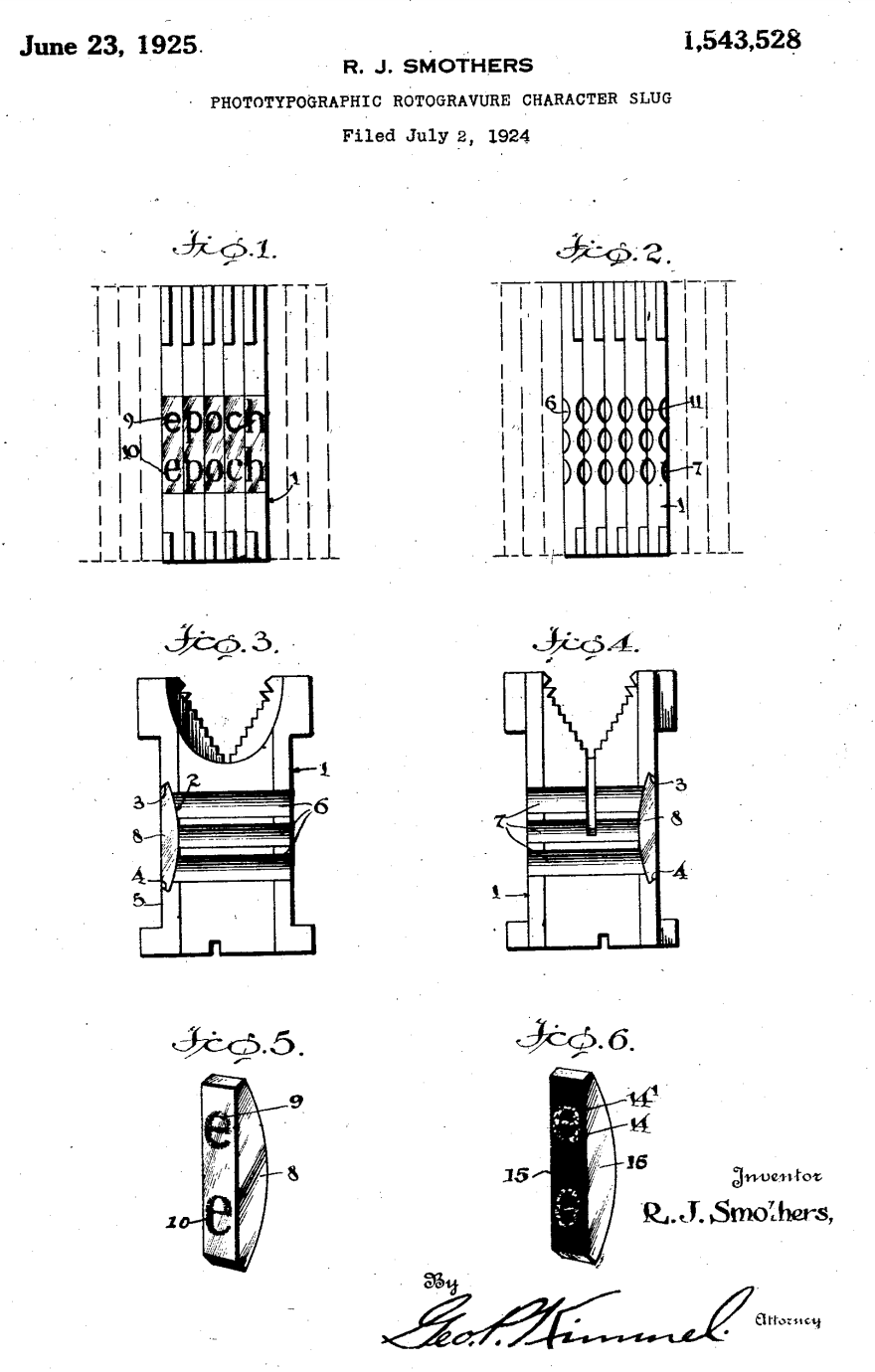

Already in 1925, R.J. Smothers received a patent regarding matrices for the Linotype with lenses for phototypography. This is the oldest reference to a typecasting machine working with light that we currently know about.

However, we have no proof that any of such machines were initially commercially available. It would take till around 1950 before this technology was introduced in the production environments of printers. In that year, the Intertype Corporation published the brochure 'New Horizons' (download). Therein, Intertype introduced and advertised their new Fotosetter as "the first keyboard-operated machine to produce photographic type composition on a commercial basis."

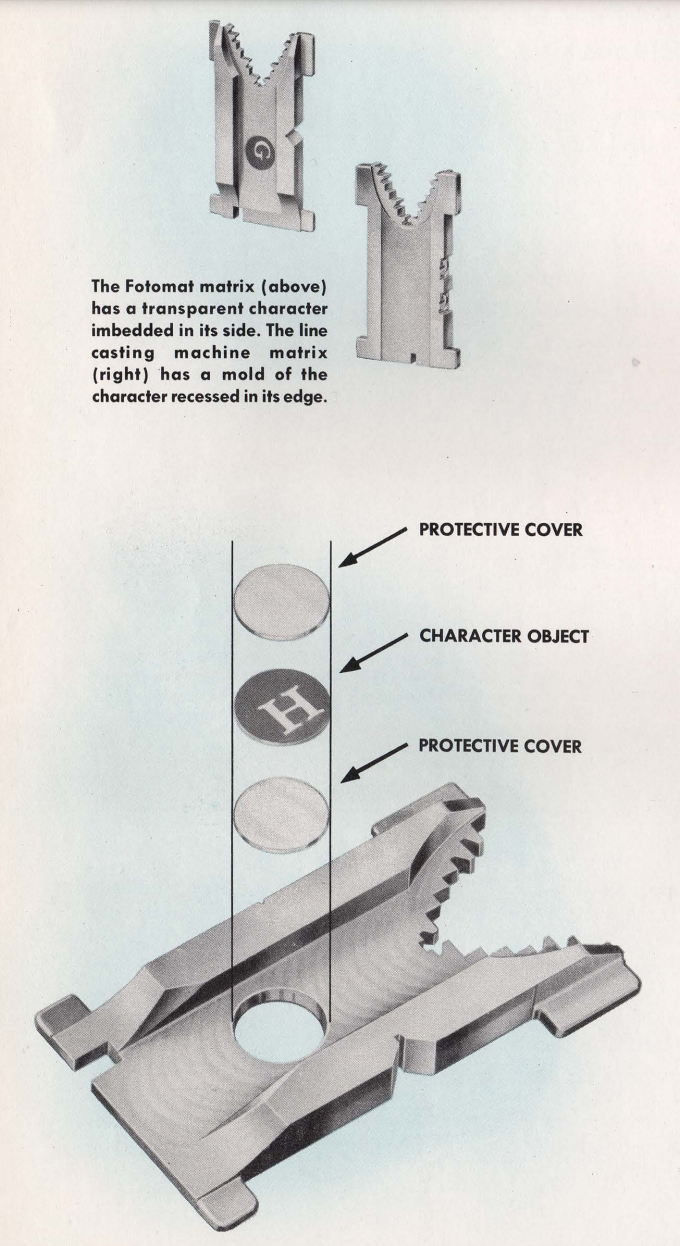

The new machines worked with adjusted matrices. These contained a transparent character imbedded in the middle, visible on both sides. Intertype named those matrices the 'fotomats':

The principles of the fotomat (Intertype Corporation, 1950).

The introduction of the fotosetter did not mean that the hot metal casting immediately became obsolete. The first products with phototypesetting weren't known for their best quality of type. It took a while before they became popular. Intertype produced at least linecasting machines till 1967 (see the page about Intertype serial numbers) and at the same year, Linotype even introduced a model for hot metal casting (see the page about the Linotype serial numbers). The Russian Leningradskii zavod poligraficheskikh mashin produced hot metal catsing machines till at least 1989! (see here).

The printing houses only gradually switched to the new technology. The most famous conversion from hot metal typesetting to phototypesetting (cold type setting) was the one from the New York Times. It only happened in 1978! The last night that the New York Times was set with hot metal typesetting was beautifully preserved in an documentary:

In the video, people are sad about moving to another technology. One of them retires instead of getting to work with the phototypesetting. This happened everywhere. People were very attached to their machines, who they cared for every day. That is probably the reason that a lot of printers kept their machine in storage, even if it had no commercial use anymore.

C 2021-2024 Maarten Renckens and other contributors. All rights reserved. All materials on this website are available for non-commercial re-use, as long as the original author is mentioned and a correct reference to this site is added. Thanks!

All materials are considered copyrighted by the author(s) unless otherwise stated. Some materials from other sources are used. If you find materials on this page which you consider not free from copyright, a notification is appreciated.

All collaborations and additional sources are more than welcome. Please contact info@maartenrenckens.com if you have materials that you deem valuable.