With different kinds of typesetting machines on the market, it is easy to ask which one is the best. The comparison between Linotype and the Typograph on this page is based upon Maarten Renckens' perception as a technician for both machines. It reflect his general experience, but it can differ per person.

The Typograph completely relies on gravity to move the matrices. While this concept looks simple, it inherently is less controllable than a rail system such as in the Linotype. For example, if the rods of the Typograph are dirty, matrices are not gliding very well. And the matrices containing capital letters, which are positioned on the lower rods which are less steep, are often not gliding very well into position. It requires a really nicely adjusted machine to ensure that everything runs well.

Also the matrices themselves are prone to damage. They hang on rods, so they can get between moving parts of the machine and bend. The matrices also hit each other when the machine is moving, possibly causing damage on fragile parts of the letter image.

Additionally, in my experience, having too many matrices on a single rod (even if there is place enoug) bends the rods. In that case, matrices unintendedly escape when the machine is moving, causing unwanted letters in a line of type.

If something goes really wrong in a Typograph, such as for example a space that is not turning well or a matrix that is bent, and the line of matrices not completely filled, the type metal is injected into the inner parts of the machine. This is called a squirt. Photo 1 illustrates how the circular spaces are surrounded by type metal, photo 2 illustrates how difficult it is to reach the type metal between all the machine parts.

Depending on the place of the squirt, chance is high that the keyboard of the machine cannot be lifted anymore. The machine then remains closed and it is really difficult and time consuming to have the type metal removed. On photo 3 and 4, it is illustrated that to remove this squirt, the keyboard was lifted by force, causing damage to the hooks of some matrices.

An operator thus had to be really careful while setting type to avoid squirts.

Photos 1, 2, 3 and 4: a squirt inside the Typograph. In this case, the hooks on some matrices were damaged to lift the keyboard to get to the type metal inside the machine.

On the Linotype, the matrices follow their predefined path and there are relatively few adjustments necessary.

The working of the Typograph relies on several springs, which can loose their strength. That probably is one reason why more levers are build in. While this provides a possibility to adjust the machine, it also involves more work and knowledge to keep the machine running smoothly, plus more ways that something can go wrong.

The Typograph always uses the front matrices first. That makes that those matrices wear out faster than the matrices on the back. The Linotype does not have this problem, as all matrices are circulated and thus used an equal number of times.

While the original prices are not known anymore, it is told that the Typograph was cheaper than a Linotype. Because the Typograph is much smaller and contains less parts, this probably is true. Old typesetters use to tell that the Typograph was used in smaller print shops. So its lower price and smaller size was one reason to go for a Typograph.

The competing companies of course also put forward the advantages of their machines in their marketing.

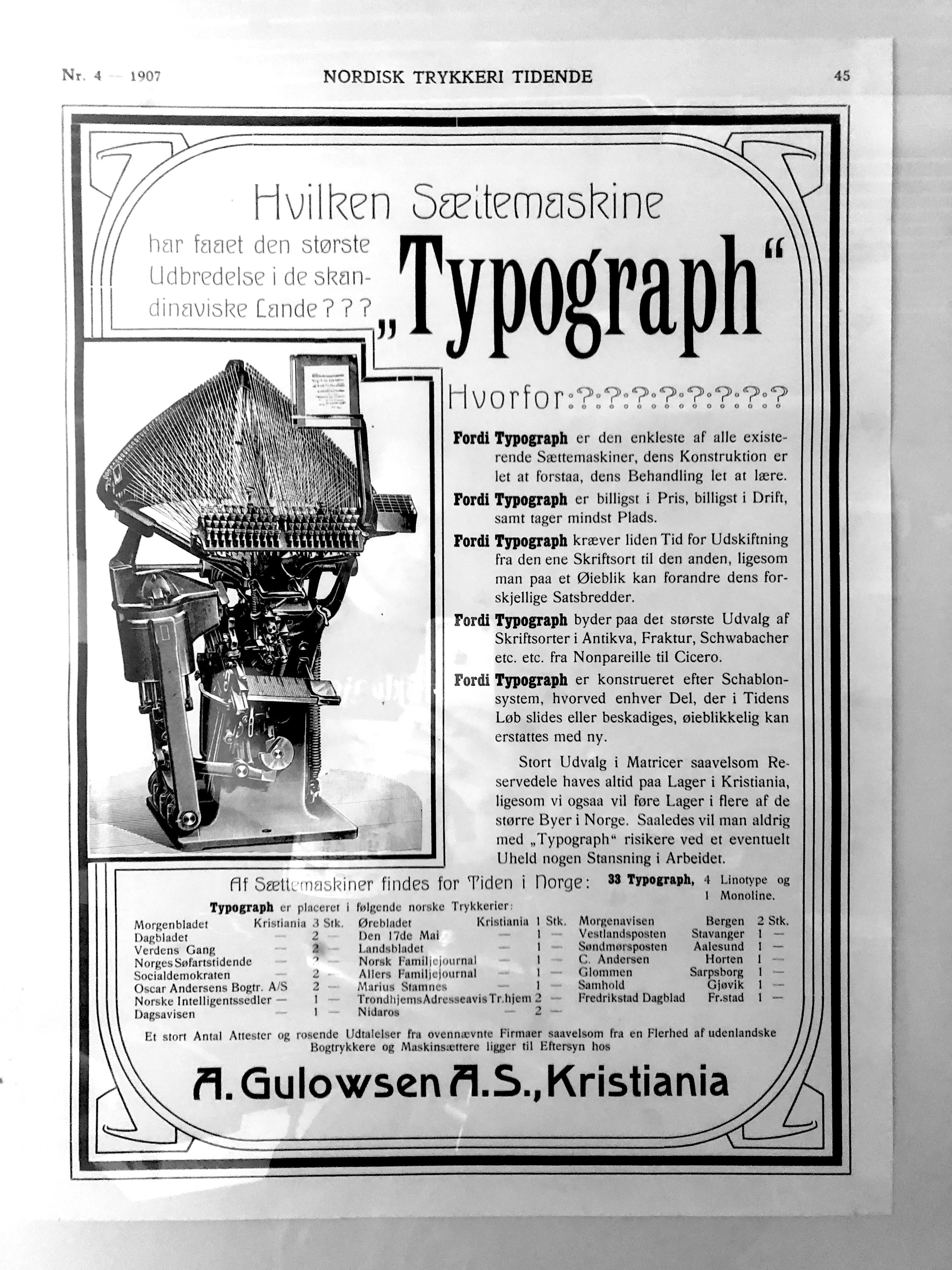

In the following Norwegian advertisement, The A. Gulowsen A.S. Company who sold Typographs brought forth the following arguments to buy a Typograph:

Of course, some arguments can be refuted, but the strongest and most remarkable argument was that there are 33 Typographs, against only 5 other competing machines. Of course, this is the situation in 1907, which we assume changed over the years, but it clearly illustrates that the Typograph was able to conquer the markets in some countries.

An official advertisement for the Typograph from the Nordic Printing Journal from 1907.

C 2021-2024 Maarten Renckens and other contributors. All rights reserved. All materials on this website are available for non-commercial re-use, as long as the original author is mentioned and a correct reference to this site is added. Thanks!

All materials are considered copyrighted by the author(s) unless otherwise stated. Some materials from other sources are used. If you find materials on this page which you consider not free from copyright, a notification is appreciated.

All collaborations and additional sources are more than welcome. Please contact info@maartenrenckens.com if you have materials that you deem valuable.