This page is a logbook about the design process of the 3D printed matrices for Linotype & Intertype machines by Maarten Renckens and Steven Renckens .

Matrices are elements moving throughout the typesetting machines. The movement means that they are prone to wearing out. But the matrices are not produced anymore, the production machines are probably gone, and the exact production process is nowhere described as far as we know. The limited information that we could trace is described on our page explaining the matrices production process.

Because no matrices are produced anymore, the original matrices will be gone at a certain point and the machines can no longer run. In order to keep the machines running, Maarten Renckens and Steven Renckens are evaluating how to create new matrices with the aid of a contemporary production process: 3D printing.

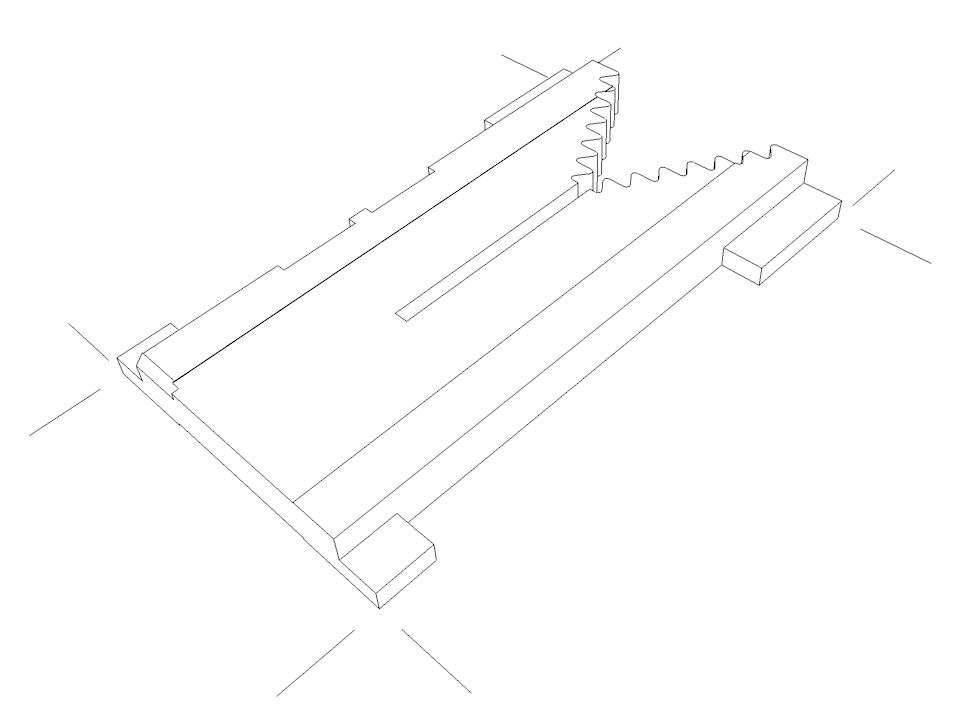

First, we want to clarify what exactly needs to be created. We measured every detail of the matrices. An article about the matrices' dimensions is in progress, the hyperlink to it will be placed here after publication.

The following video illustrates very well how a 3D printer is working (the speed of the movie is accelerated):

The printing head moves with instructions containing x, y and z coordinates. In this printer, the printing head is moving in one direction, the base is moving in another direction, and the printing head can go up when needed.

This is a visual sample created with a small hobby printer, but actual matrices need to be created with a 3D printer that can handle metal. Those 3D printers work according the same basic idea, but they melt granules (small little grains) instead of plastic.

Nobody doubts that 3D printing is a beautiful technique, because it is fast and can produce the most complex shapes.

However, 3D printing has its own specific limitations. On small scales, it won't reach the same quality as other production processes, if it is able to print the object at all. Corners will be slightly rounded and the final print is not completely smooth. The causes are the granules within the printer. A rough polishing is not desirable for matrices, as they should fit next to each other (the lead should not have an opening to flow in-between the matrices) and the typeface needs to be of the highest quality possible (a distorted typeface wouldn't be comfortable to read). After all, the matrices still contain a mold in which lead is poured, and it is only with that lead that the printer will print.

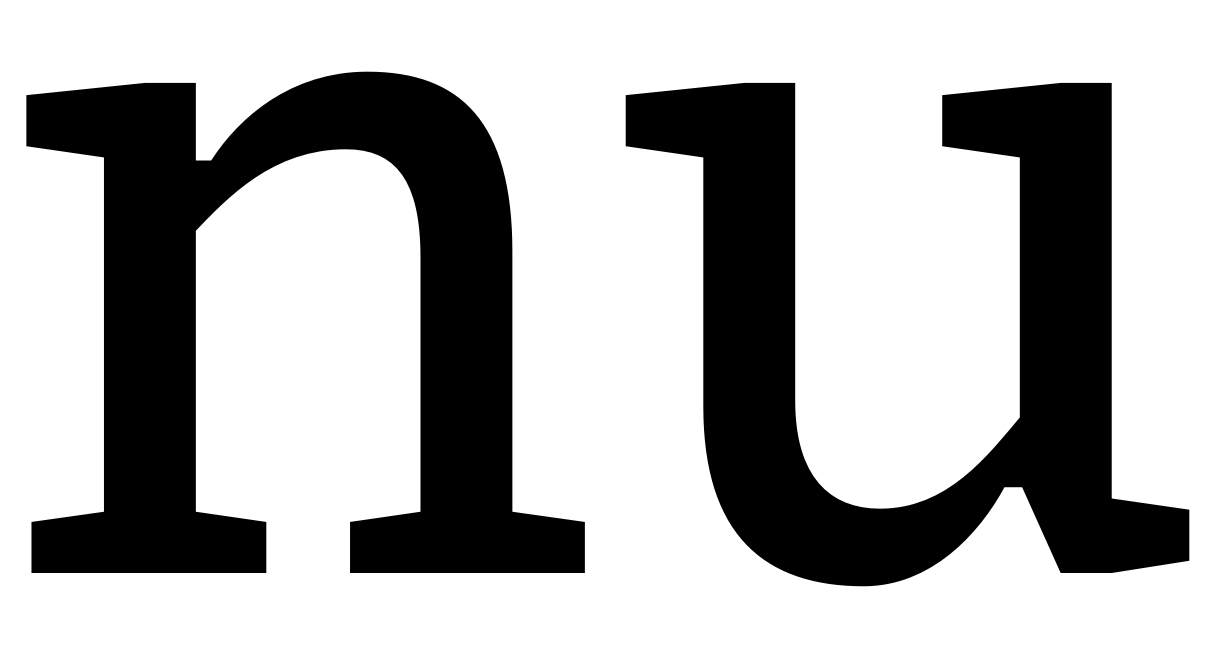

To compensate for the loss of quality in a 3D print, Maarten Renckens developed the typeface 'A Line of type'. This typeface features design solutions to overcome the worst quality loss in 3D printing, such as large counters and a wide design.

Illustrations: Details of the typeface developed to be printed

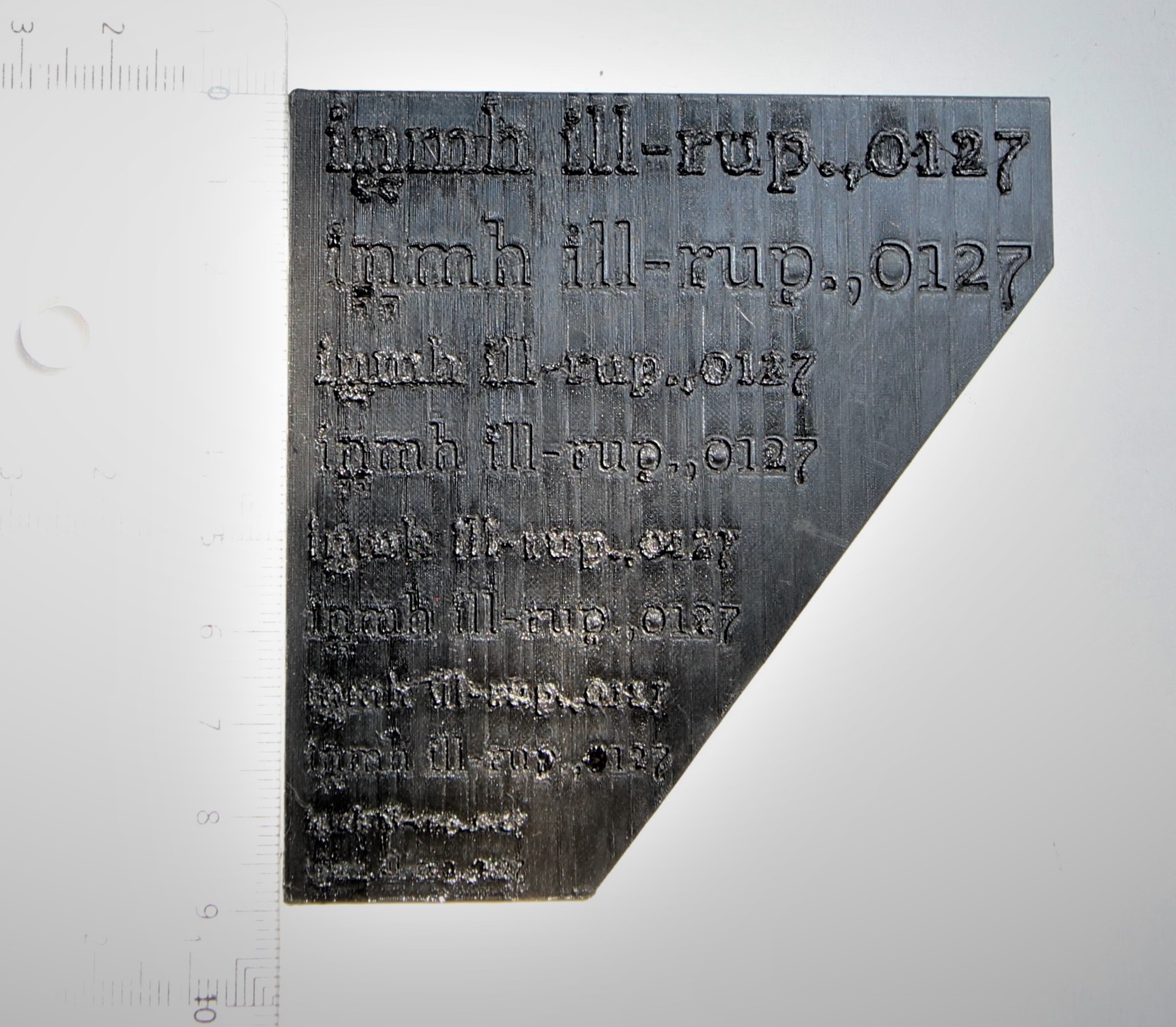

When 3D printing this typeface as an exercise, it is clearly seen how the quality lowers on smaller scales:

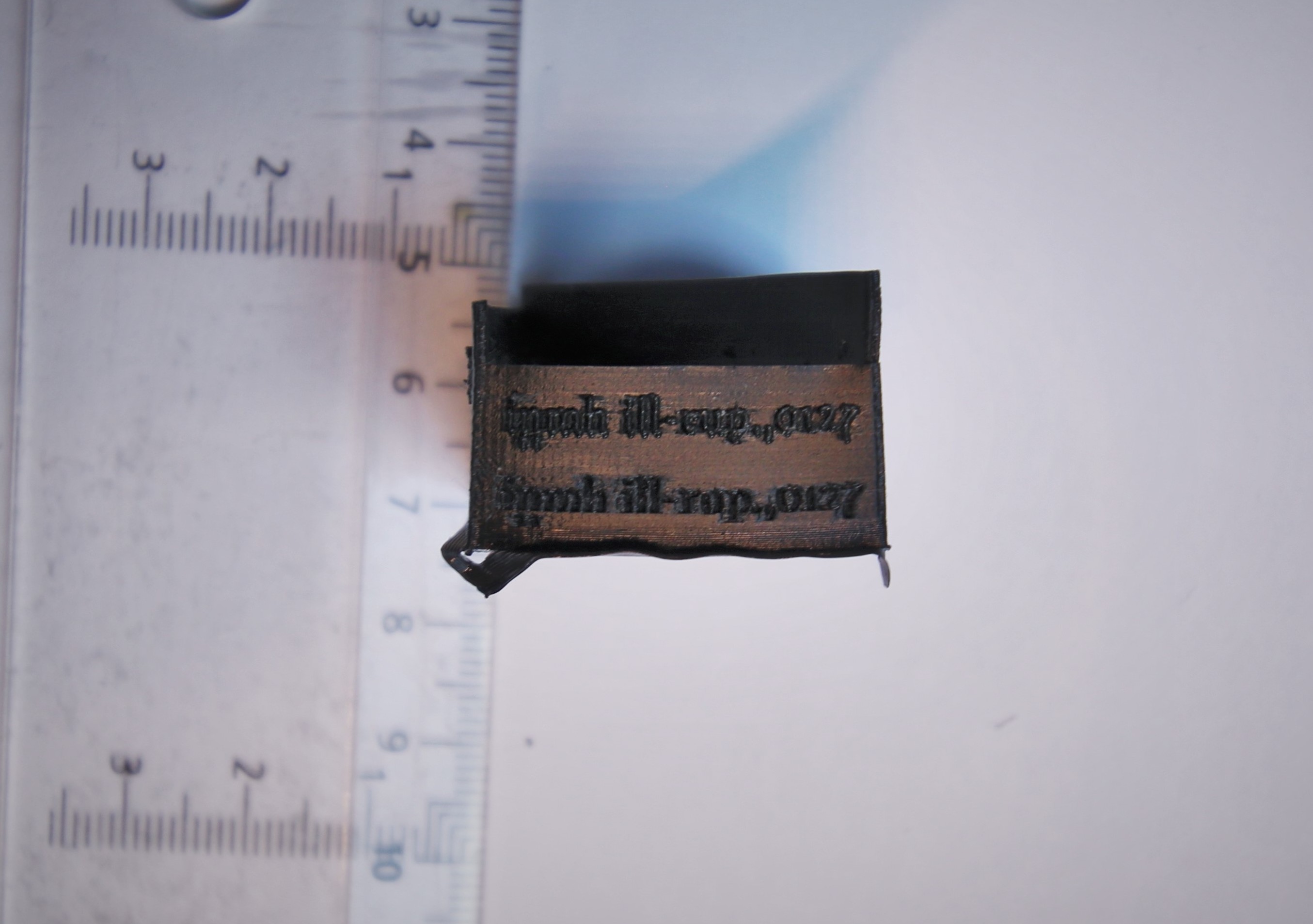

Photo: experiments printed in plastic. Notice how the details are less refined as the letters get smaller

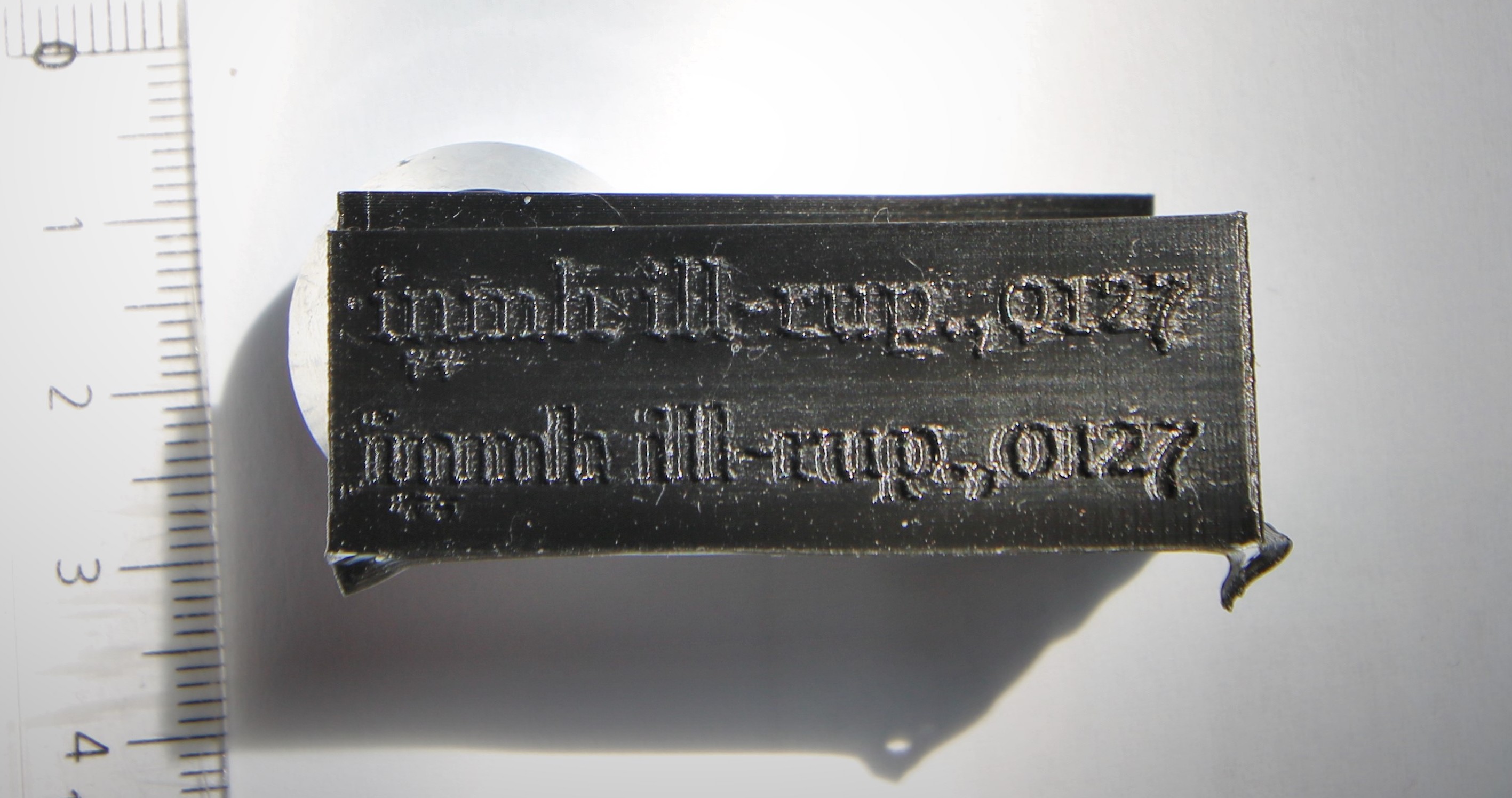

The previous print was flat. We did the same exercise, but printed vertically. As you can see, the letters reach a slighty higher quality. There are fewer strings of molten material connecting the letters. Still, the quality remains low:

Photos: experiments printed in plastic. Depending on the print direction, the quality of the letters differs

Other printers, and specifically 3D printers printing metal reach a higher quality.

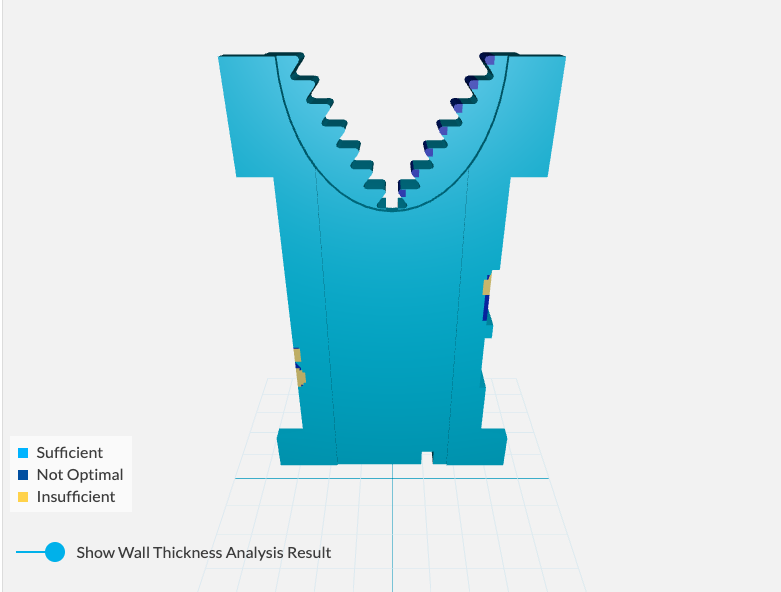

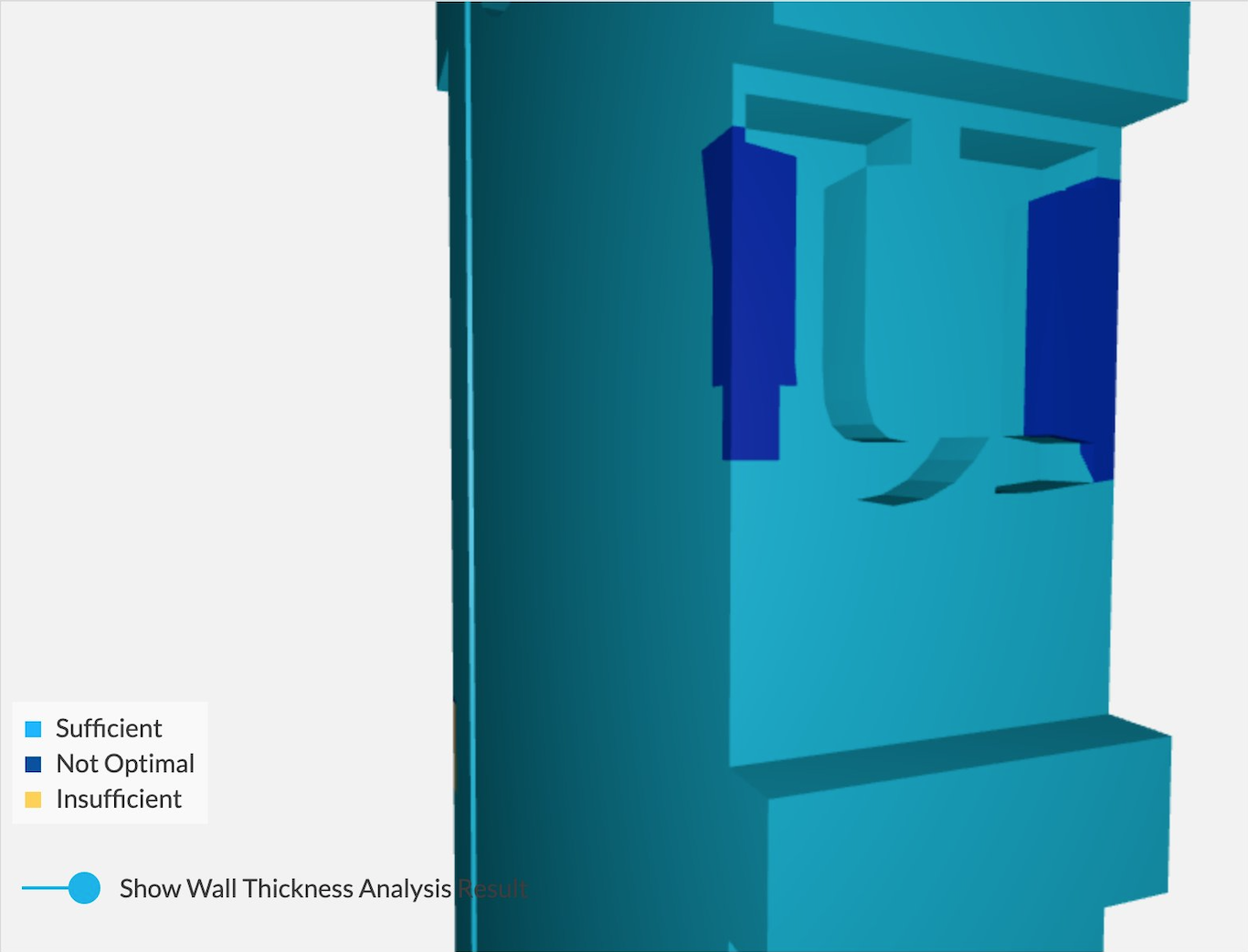

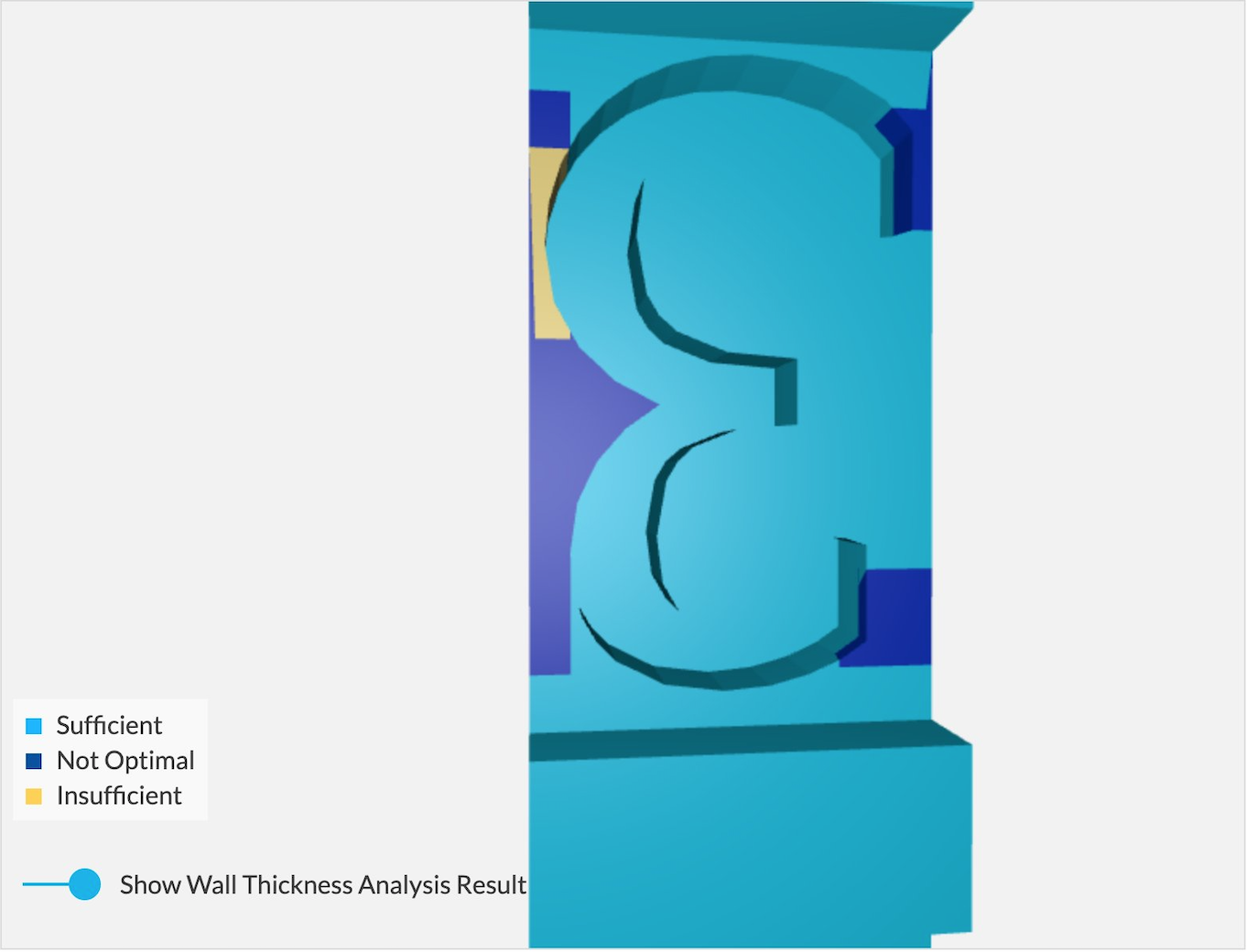

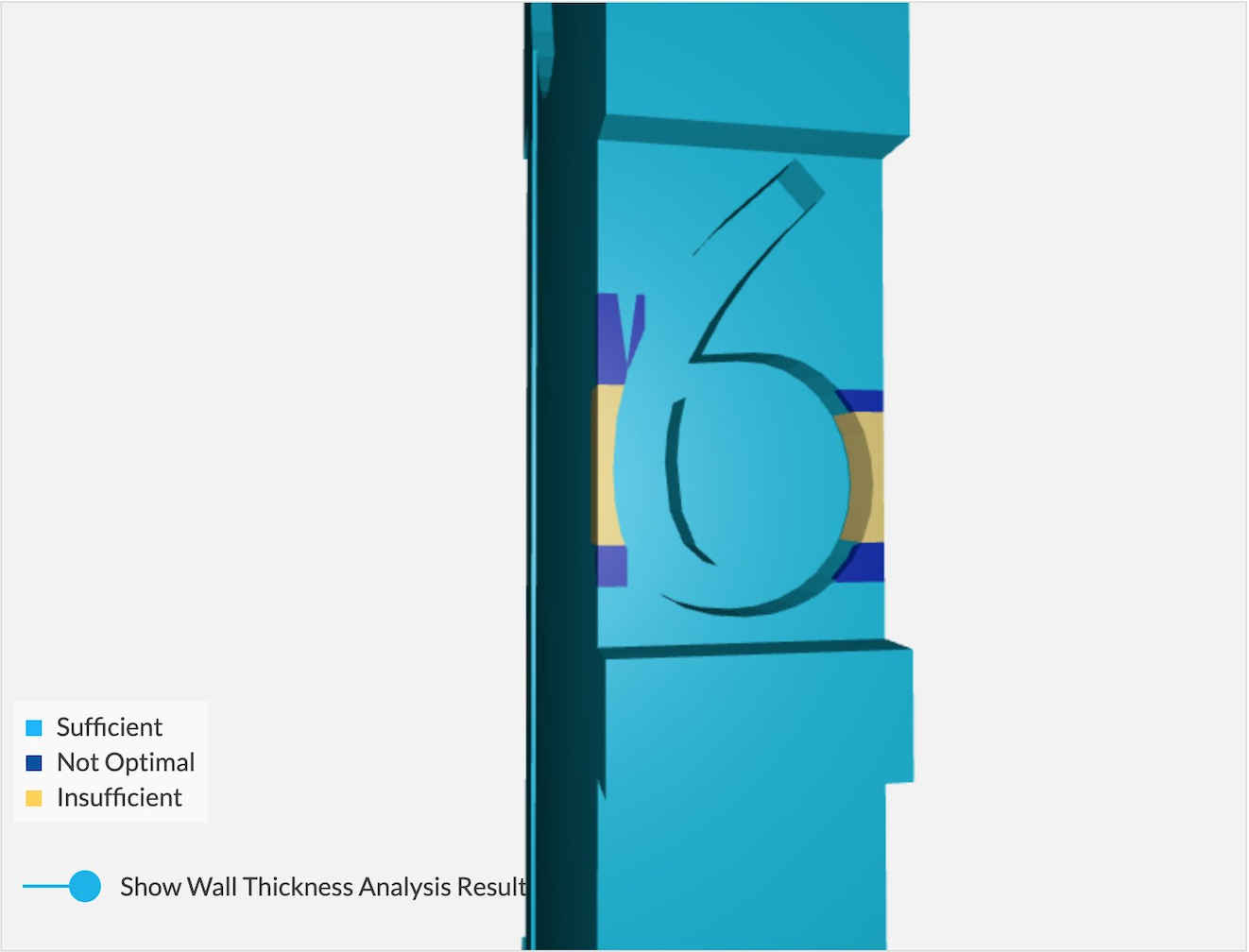

But even with a typeface designed to counter some of the quality loss, there are more difficulties to overcome. The printing company does review the 3D models before printing, as can be seen here. Based on their experience, they advise a minimum wall thickness of 0.6 mm. They also note that dimensional deviations are possible: dimensional accuracy for brass is ±5% (with a lower limit of ±0.15 mm). It is visible in the images which parts they expect to provide trouble (blue), and which parts are not feasible (yellow):

Illustrations: the errors provided by the 3D printer. Blue means that it is not an optimal thickness, yellow means that the thickness is to small to be printed

The complete guidelines for 3D printing are available at https://i.materialise.com/en/3d-printing-materials/brass/design-guide#WallThickness.

Some 3D printers are able to print in brass, the same material as the original matrices. However, an additional problem is that it isn't sure yet that the printed brass has the same quality as the original brass because the ratio of the materials can be different. At the moment, we are not yet in the phase of evaluating the material. But when we are, the matrices need to be tested when used in short time periods, namely the heating to 280 degrees, and in long time periods, namely how long they will last after extensive usage.

So at the moment, we are able to 3D print the matrices:

Photo: three newly printed matrices compared to an original one

There is a lot of work to do. At the moment, we are testing new prints. The first tests point out that the 3D printed brass is able to withstand the required heat of those machines. Additionally, we need to test if a typeface can be developed that suits contemporary 3D printers.

We are open for other production processes/mixed production processes as well. In case we find a suitable one, the experience gained in this exercise could prove to be useful.

C 2021-2024 Maarten Renckens and other contributors. All rights reserved. All materials on this website are available for non-commercial re-use, as long as the original author is mentioned and a correct reference to this site is added. Thanks!

All materials are considered copyrighted by the author(s) unless otherwise stated. Some materials from other sources are used. If you find materials on this page which you consider not free from copyright, a notification is appreciated.

All collaborations and additional sources are more than welcome. Please contact info@maartenrenckens.com if you have materials that you deem valuable.